Understanding fMRI: How Brain Imaging Reveals Nervous System Function

Functional magnetic resonance imaging, commonly known as fMRI, has revolutionized our understanding of the brain and nervous system. This powerful imaging technique allows researchers and clinicians to observe brain activity in real-time, providing unprecedented insights into how our neural networks function. Whether you’re a patient preparing for a scan, a student exploring neuroscience, or simply curious about brain imaging technology, this guide will help you understand what fMRI can—and cannot—reveal about nervous system function.

How fMRI Works: The BOLD Signal

Unlike traditional MRI, which captures static images of brain structure, fMRI measures brain activity by detecting changes in blood flow. The technology relies on a principle called the Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) signal.

When neurons in a specific brain region become active, they consume oxygen. The body responds by increasing blood flow to that area, delivering oxygen-rich hemoglobin. Here’s where the physics becomes fascinating: oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin have different magnetic properties. Oxygenated hemoglobin is diamagnetic, while deoxygenated hemoglobin is paramagnetic. The fMRI scanner detects these magnetic differences, creating a map of where blood flow—and therefore neural activity—is occurring.

The BOLD signal doesn’t measure neural activity directly. Instead, it captures the hemodynamic response, which typically peaks about 5-6 seconds after neurons fire. This temporal delay is important to understand when interpreting fMRI results. The spatial resolution of modern fMRI is impressive, capable of detecting activity in regions as small as 1-2 millimeters, though standard clinical scans typically use larger voxels for practical reasons.

What fMRI Can Show

fMRI excels at revealing which brain regions activate during specific tasks or stimuli. Researchers use this capability to map cognitive functions, emotional responses, and sensory processing. Key applications include:

Functional brain mapping: Before neurosurgery, fMRI helps surgeons identify critical areas controlling speech, movement, and other essential functions. This pre-surgical mapping can significantly reduce the risk of post-operative deficits.

Understanding neural networks: Modern fMRI analysis examines not just individual brain regions but how different areas communicate. Resting-state fMRI, performed while subjects lie quietly in the scanner, reveals the brain’s default mode network and other intrinsic connectivity patterns.

Research into neurological and psychiatric conditions: fMRI studies have illuminated how conditions like depression, anxiety, chronic pain, and various vagus nerve conditions affect brain function and connectivity.

Investigating autonomic function: The brain regions controlling autonomic processes—including heart rate, digestion, and stress responses—can be visualized during fMRI. This has proven particularly valuable in bioelectronic medicine research, where understanding brain-body communication is essential.

What fMRI Cannot Show

Despite its power, fMRI has important limitations that both researchers and patients should understand:

It doesn’t read thoughts: While fMRI can show which brain regions are active, it cannot decode specific thoughts, memories, or intentions. Claims about “mind reading” technology based on fMRI are greatly exaggerated.

The BOLD signal is indirect: fMRI measures blood flow changes, not electrical neural activity. The relationship between the BOLD signal and actual neuronal firing is complex and not perfectly understood.

Temporal resolution is limited: Neural events occur in milliseconds, but the hemodynamic response unfolds over seconds. For tracking rapid brain dynamics, techniques like EEG or MEG are more appropriate.

Individual variability: Brain anatomy and function vary between individuals. What appears as “normal” activation in group studies may not apply to every person.

Motion sensitivity: Even small head movements can corrupt fMRI data. This presents challenges when scanning children, anxious patients, or those with movement disorders.

Research vs. Clinical Applications

The use of fMRI differs substantially between research and clinical settings.

In research, fMRI is an exploratory tool used to investigate hypotheses about brain function. Studies typically involve groups of participants, and results are analyzed statistically to identify trends. Research applications span from basic neuroscience—understanding how we perceive, think, and feel—to applied questions about disease mechanisms and treatment effects.

Clinical fMRI applications are more focused and must meet higher standards for individual patient interpretation. The most established clinical use is pre-surgical mapping, where fMRI helps neurosurgeons plan tumor removals or epilepsy surgeries. Some centers also use fMRI to assess language lateralization or evaluate patients with disorders of consciousness.

The gap between research findings and clinical utility remains significant. Many exciting research discoveries about fMRI biomarkers for psychiatric conditions or neurological diseases have not yet translated into validated clinical tools. This translation requires extensive validation, standardization, and regulatory approval.

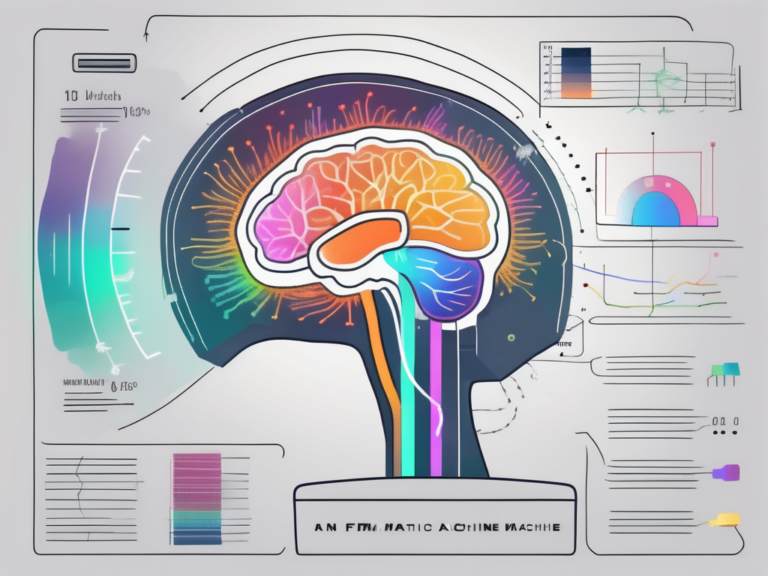

fMRI Insights into Vagus Nerve Stimulation and Autonomic Function

One particularly productive area of fMRI research examines how vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) affects brain activity. The vagus nerve, the longest cranial nerve, serves as a major communication highway between the brain and body. fMRI studies have revealed that VNS produces widespread effects on brain function, including:

Activation changes in the brainstem nuclei where vagal afferents first synapse, particularly the nucleus tractus solitarius. These changes propagate to higher brain regions involved in emotion regulation, including the amygdala, insula, and prefrontal cortex.

Modulation of the default mode network, which is often dysregulated in depression and other conditions that VNS is used to treat. fMRI evidence suggests that VNS may help normalize abnormal connectivity patterns.

Changes in autonomic control centers that correlate with improvements in heart rate variability and other physiological measures. This brain-body connection is central to understanding how neuromodulation therapies produce their effects.

These fMRI findings have helped establish the neurobiological basis for vagus nerve stimulation therapies and guide the development of next-generation devices and protocols.

The Future of fMRI

fMRI technology continues to advance. Higher field strength magnets (7 Tesla and beyond) offer improved resolution. New analysis methods, including machine learning approaches, extract more information from fMRI data. Real-time fMRI neurofeedback allows subjects to learn to modulate their own brain activity, with potential therapeutic applications.

As our understanding of the BOLD signal deepens and analysis techniques improve, fMRI will likely play an expanding role in both research and clinical care. For now, it remains our most powerful window into the living, functioning human brain—a technology that has fundamentally transformed neuroscience and continues to reveal the remarkable complexity of nervous system function.

]]>